Released 1981: The IBM Personal Computer (model 5150, best known as the IBM PC) is the first computer released in the IBM PC model line and the basis for the IBM PC compatible de facto standard. Released on August 12, 1981, it was created by a team of engineers and designers directed by Don Estridge in Boca Raton, Florida. The machine was based on open architecture and a substantial market of third-party peripherals, expansion cards and software grew up rapidly to support it.

Facts

- Type: Personal computer

- Manufacturer: IBM

- Released: August 12, 1981

- Discontinued: April 2, 1987

- OS: IBM PC DOS, IBM BASIC (built in), CP/M-86, UCSD p-System

- CPU: Intel 8088 @ 4.77 MHz

- Memory: 16 KB up to 64 KB or 64 KB up to 256 KB , expandable

- Video : IBM MDA (monochrome) or IBM CGA (color), expandable

- Audio: PC speaker (1 bit)

- Input: IBM Model F 83-key keyboard (XT keyboard)

- Removable media: Up to two 5.25″ 160KB (ss) or 320KB (ds) floppy drives, port for tape recorder

- Internal media: From 1983, optional hard disk drive

- FPU: Optional Intel 8087

- Expansion slots: 5 x ISA-8 bit, optional IBM 5161 Expansion unit

- I/O: Optional serial and parallel ports

- Predecessor: IBM System/23 Datamaster

- Successor: IBM Personal Computer XT

The PC had a substantial influence on the personal computer market. The specifications of the IBM PC became one of the most popular computer design standards in the world, and the only significant competition it faced from a non-compatible platform throughout the 1980s was from the Apple Macintosh product line. The majority of modern personal computers are distant descendants of the IBM PC.

The term personal computer was in use long before the IBM PC. Because of the name “IBM Personal Computer” for IBM model 5150 and its widespread rapid success, the term “PC” became quickly to mean more specific a microcomputer compatible with IBM PC.

Prior to the 1980s, IBM had largely been known as a provider of business computer systems. As the 1980s opened, their market share in the growing minicomputer market failed to keep up with competitors, while other manufacturers were beginning to see impressive profits in the microcomputer space. The market for personal computers was dominated at the time by Tandy, Commodore and Apple. The microcomputer market was large enough for IBM’s attention, with $15 billion in sales by 1979 and projected annual growth of more than 40% during the early 1980s. Other large technology companies had entered it, such as Hewlett-Packard, Texas Instruments and Data General, and some large IBM customers were buying Apples.

As early as 1980 there were rumors of IBM developing a personal computer, possibly a miniaturized version of the IBM System/370, and Matsushita acknowledged publicly that it had discussed with IBM the possibility of manufacturing a personal computer in partnership, although this project was abandoned. The public responded to these rumors with skepticism, owing to IBM’s tendency towards slow-moving, bureaucratic business practices tailored towards the production of large, sophisticated and expensive business systems. As with other large computer companies, its new products typically required about four to five years for development, and a well publicized quote from an industry analyst was, “IBM bringing out a personal computer would be like teaching an elephant to tap dance.”

IBM had previously produced microcomputers, such as 1975’s IBM 5100, but targeted them towards businesses; the 5100 had a price tag as high as $20,000. Their entry into the home computer market needed to be competitively priced. In 1980, IBM president John Opel, recognizing the value of entering this growing market, assigned William C. Lowe to the new Entry Level Systems unit in Boca Raton, Florida. Market research found that computer dealers were very interested in selling an IBM product, but they insisted the company use a design based on standard parts, not IBM-designed ones so that stores could perform their own repairs rather than requiring customers to send machines back to IBM for service.

Atari proposed to IBM in 1980 that it act as original equipment manufacturer for an IBM microcomputer, a potential solution to IBM’s known inability to move quickly to meet a rapidly changing market. The idea of acquiring Atari was considered but rejected in favor of a proposal by Lowe that by forming an independent internal working group and abandoning all traditional IBM methods, a design could be delivered within a year and a prototype within 30 days. The prototype worked poorly but was presented with a detailed business plan which proposed that the new computer have an open architecture, use non-proprietary components and software, and be sold through retail stores, all contrary to IBM practice. It also estimated sales of 220,000 computers over three years, more than IBM’s entire installed base.

This swayed the Corporate Management Committee, which converted the group into a business unit named “Project Chess,” and provided the necessary funding and authority to do whatever was needed to develop the computer in the given timeframe. The team received permission to expand to 150 people by the end of 1980.

Development

The development was kept under a policy of strict secrecy, with none of the other IBM divisions knowing what was going on. Several CPUs were considered, including the Texas Instruments TMS9900, Motorola 68000 and Intel 8088. The 68000 was considered the best choice, but was not production-ready like the others. The IBM 801 RISC processor was also considered, since it was considerably more powerful than the other options, but rejected due to the design constraint to use off-the-shelf parts.

IBM chose to use the less capable Intel 8088 processor over the binary compatible 8086 because Intel offered a better price for the former and could provide more units, and the 8088’s 8-bit bus reduced the cost of the rest of the computer. The 8088 had the advantage that IBM already had familiarity with it from designing the IBM System/23 Datamaster. The 62-pin expansion bus slots (ISA) were also designed to be similar to the Datamaster slots, and its keyboard design and layout would become the Model F keyboard (XT keyboard), but otherwise the PC design differed in many ways.

The 8088 motherboard was designed in 40 days, with a working prototype created in four months, demonstrated in January 1981. The design was essentially complete by April 1981, when it was handed off to the manufacturing team. PCs were assembled in an IBM plant in Boca Raton, with components made at various IBM and third party factories. The monitor was an existing design from IBM Japan, the printer was manufactured by Epson. Because none of the functional components were designed by IBM, they obtained no patents on the PC.

Many of the designers were computer hobbyists who owned their own computers, including many Apple II owners, which influenced the decisions to design the computer with an open architecture and publish technical information so others could create software and expansion slot peripherals. During the design process IBM avoided vertical integration as much as possible, choosing for example to license Microsoft BASIC despite having a version of BASIC of its own for mainframes, due to the better existing public familiarity with the Microsoft version.

Operating system

CP/M of Digital Research was an early “de facto standard” of a general 8-bit operating system. CP/M was designed to be adapted to most personal computers which ran on either an Intel 8080/85 or an Zilog Z80 processor. Digital Research was working on a 16-bit version for the 8088 and 8086 processor (CP/M-86). IBM had planned to use CP/M-86 for their new computer. Somehow, IBM failed to get the agreement they needed in time. There are some conflicting stories about the exact details about a incident when IBM went to meet with Digital Research. Probably there had been an misunderstanding about the meeting was scheduled for AM or PM. IBM showed up at ten o’clock in the morning while Digital Research thought it was scheduled for ten o’clock in the evening.

Jack Sams (IBM): “IBM just couldn’t get Kildall (Gary Kildall – Digital Research) to agree to spend the money to develop a 16-bit version of CP/M in the tight schedule IBM required.”

IBM talked with Microsoft about their problem, and Microsoft’s Gates, Paul Allen, and Kay Nishi discussed what to do. Paul Allen knew of Seattle Computer Products (SCP) and their QDOS. Kay Nishi was the one most in favor of Microsoft getting into the operating systems, and Allen says in his autobiography that Gates was less enthusiastic.

IBM had experienced legal problems with 3rd party program code in the past and wanted Microsoft to purchase QDOS. Bill Gates, Steve Ballmer and Bob O’Rear met with IBM and agreed that Microsoft would handle the operating system development for the IBM PC.

Allen contacted SCP owner Rod Brock about licensing QDOS and told them they already had the first customer, without revealing who it was. Microsoft got an agreement about licensing QDOS for $10.000 and in addition $15.000 for each OEM customer. Microsoft paid $25.000 and had an operating system for their “secret customer”, IBM.

Tim Paterson was then hired in from SCP by Microsoft, to develop QDOS into PC DOS for the upcoming IBM PC. This work happened over the next eleven months. The development was closely supervised by IBM engineers. Almost daily, Paterson shipped development versions to Boca Raton for IBM’s approval, and IBM would instantly return modifications.

Paterson finished PC-DOS in July 1981, one month before the IBM PC was officially launched (QDOS had now become PC DOS).

CP/M-86 became available as an option for the IBM PC about six months after its launch. Digital Resource considered suing over IBM PC DOS, but IBM offered to make CP/M-86 available on the IBM PC.

Microsoft looses a legal battle with SCP over QDOS in 1986 and pays SCP $925.000 in addition for QDOS. (Had SCP only been aware of Microsoft’s “secret customer” and their relationship, the price for 86-DOS would have been set much higher in the first place.)

I’ve written an own article about IBM PC DOS, see: The History of DOS

Release

The IBM PC was released on August 12, 1981 after a 12 month development. Pricing started at USD 1,565 for a configuration with 16K RAM, Color Graphics Adapter (CGA), and no disk drives. The price was designed to compete with comparable machines in the market. For comparison, the Datamaster, announced two weeks earlier as IBM’s least expensive computer, cost $10,000. IBM’s marketing campaign licensed the likeness of Charlie Chaplin’s character “The Little Tramp” for a series of advertisements based on Chaplin’s movies, played by Billy Scudder.

The PC was IBM’s first attempt to sell a computer through retail channels rather than directly to customers. Because IBM did not have retail experience, they partnered with the retail chains ComputerLand and Sears Roebuck who became the main outlets for the PC. More than 190 ComputerLand stores already existed, while Sears was in the process of creating a handful of in-store computer centers for sale of the new product.

Reception was overwhelmingly positive, with sales estimates from analysts suggesting billions of dollars in sales over the next few years, and the IBM PC immediately became the talk of the entire computing industry. Dealers were overwhelmed with orders, including customers offering pre-payment for machines with no guaranteed delivery date. By the time the machine was shipping, the term “PC” was becoming a household name.

Reception

Sales exceeded IBM’s expectations by as much as 800%, shipping 40,000 PCs a month at one point. The company estimated that 50 to 70% of PCs sold in retail stores went to the home. In 1983 they sold more than 750,000 machines, while DEC, a competitor whose success among others had spurred them to enter the market, had sold only 69,000 machines in that period. Software support from the industry grew instantly, with the IBM nearly instantly becoming the primary target for most microcomputer software development. One publication counted 753 software packages available a year after the PC’s release, four times as many as the Macintosh had a year after release. Hardware support also grew rapidly, with 30-40 companies competing to sell memory expansion cards within a year.

By 1984, IBM’s revenue from the PC market was USD 4 billion, more than twice that of Apple. A 1983 study of corporate customers found that two thirds of large customers standardizing on one computer chose the PC, compared to 9% for Apple. A 1985 Fortune survey found that 56% of American companies with personal computers used PCs, compared to Apple’s 16%.

Almost as soon as the PC reached the market, rumors of clones began, and the first PC compatible clones was released less than a year after the PC’s debut.

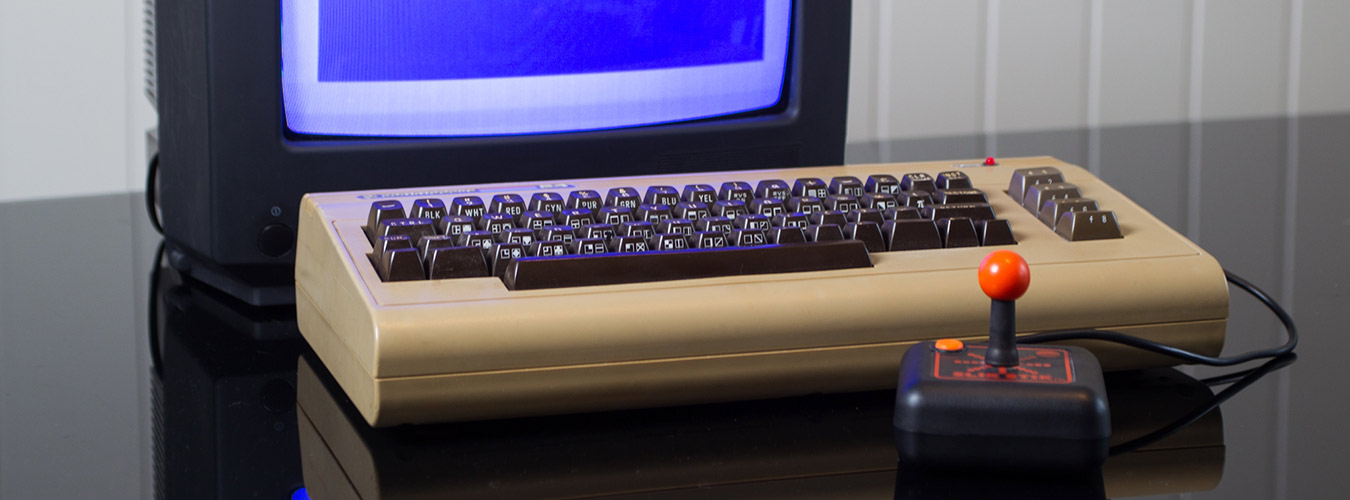

My IBM Personal Computer

I’ve swapped a vintage mainframe oscilloscope for my IBM PC 5150 with the IBM 5151 12″ monochrome monitor, but the keyboard was missing. Turned out the seller had an hobby of repair and collect old radios and oscilloscopes. It was a local pickup, only five minutes a way from my workplace, so no shipping cost. In another trade I’ve got an IBM PC XT with a correct Model F keyboard to use with this computer.

After doing my usual cleaning procedures and removing marks, the machine and monitor looked great. The machine fired up and got display on screen. It started up with some error codes and then automatically went into IBM Basic which are built into ROM.

The error codes was for memory, keyboard and hard disk or hard disk controller.

Hard disk: The hard disk was not spinning up and appeared dead. I’ve removed the hard disk logic board and rotated the spindle clockwise by hand and also put a very small drop of WD40 oil on the axis. After some “fiddling”, the hard disk span up and the machine booted into IBM PC DOS. The hard disk is noisy, but works.

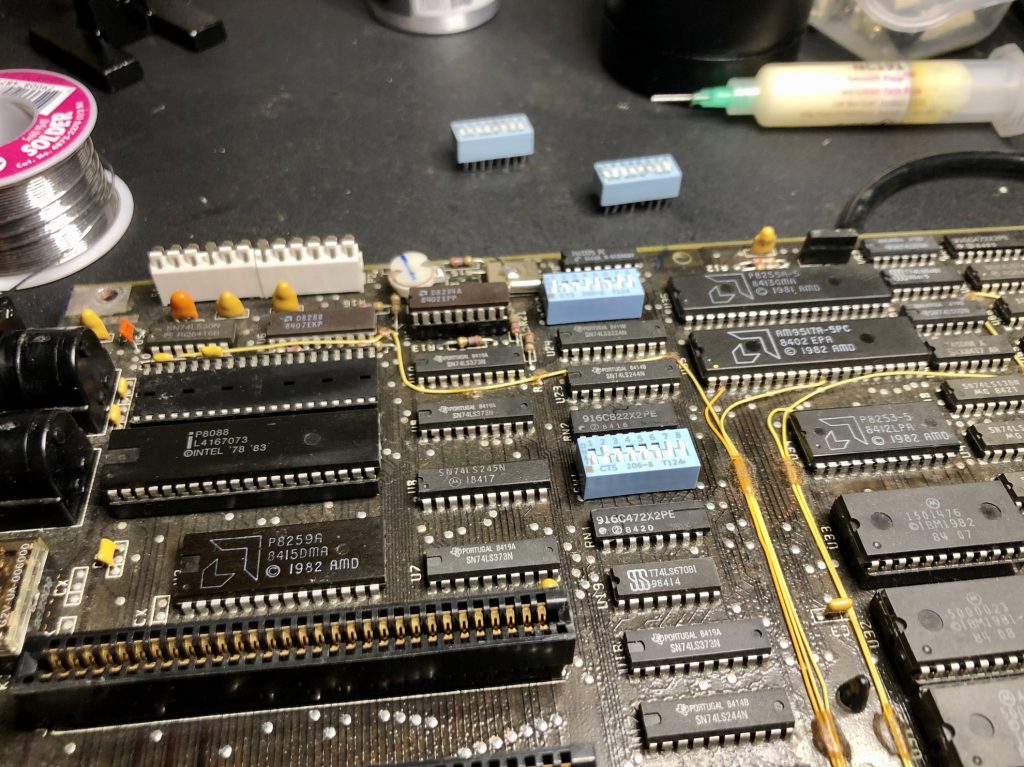

Memory: The DIP-switch configuration for the memory was wrong, after sorting this out I still got 4098 201 error code. First I though it was re-reseating the RAM chips in its sockets that fixed it, but found out the DIP switches was worn and need to be tickled with to get rid of the error. I then replaced the dip-switches SW1 and SW2 with new ones. Problem solved.

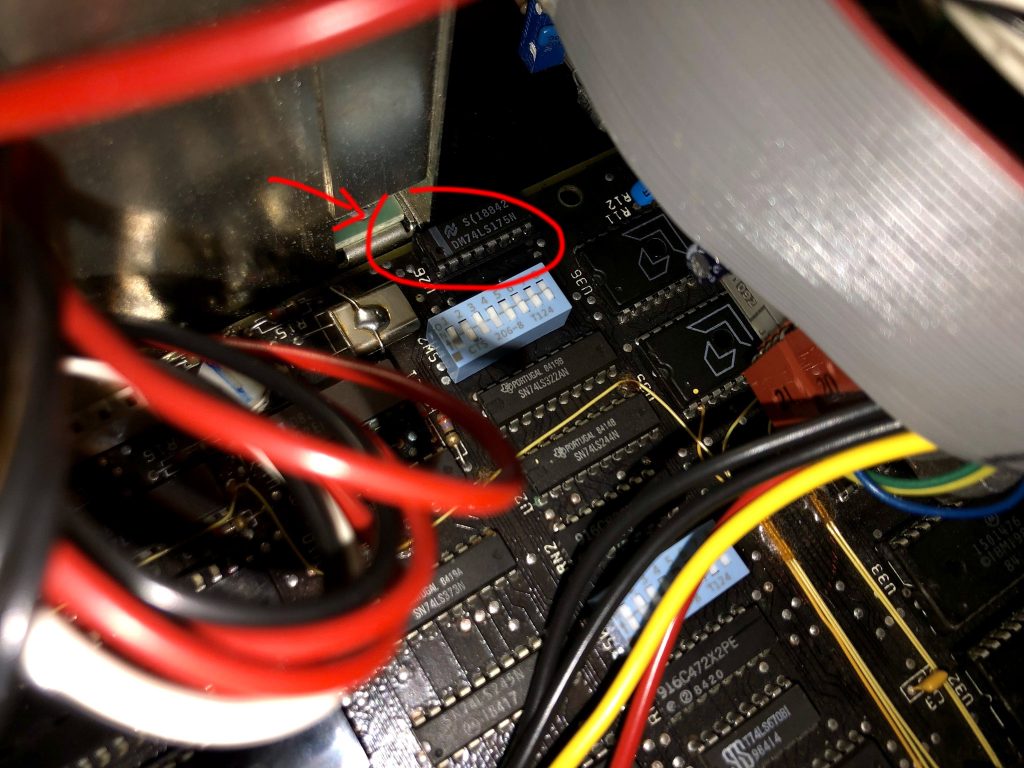

Keyboard: The keyboard would only work correctly for a few minutes, then fail completely. Machine then needed to be turned off for hours for keyboard to work a couple of minutes again. I’ve tested the keyboard on a IBM PC XT I’ve got, and it was all working good. So the problem was not on the keyboard side. I’ve re-soldered the DIN connector on the motherboard and replaced the two ceramic 47pF disk capacitors behind the DIN-connector. Didn’t help. I’ve got the diagram scheme for the keyboard circuitry on the main board, and re-soldered the IC’s involved. Didn’t help either. I’ve then used a cooling spray on one IC at a time, and quickly found that the logic IC on U26 (74ls175) was to blame. I’ve removed the faulty IC, and soldered in a socket for a new IC. Finally, problem solved.

Floppy drive: Floppy drive was not working reliable and was only able to read a few floppies. I’ve cleaned it and lubricated some moving parts and checked if the screws for the reader head assembly was tightened. Then softly cleaned the reader heads with a cotton tip and some alcohol for around two minutes, a few seconds is not always enough.

I adjusted the rotation speed by using a florescent lamp with the calibration marks on the spinner wheel underneath. The florescent lamps “flashes” 50Hz and the calibration streaks on the wheel should be almost standing still when its running. The floppy drive could now reliably read diskettes that was formatted using the same drive, but not floppies diskettes made on other drives so well.

I had connected the floppy drive to a 486 PC and ran a program named Image disk which have option to align floppy drives. I had to loosen three holding screws in order to adjust the reader head alignment. I did a small adjustment, and the drive was able to reliably read floppy disks formatted on other known well working drives. Success!

One thought on “IBM Personal Computer”